What do Georgian Bay, Newfoundland, Antarctica, and the Ivory Coast all have in common?

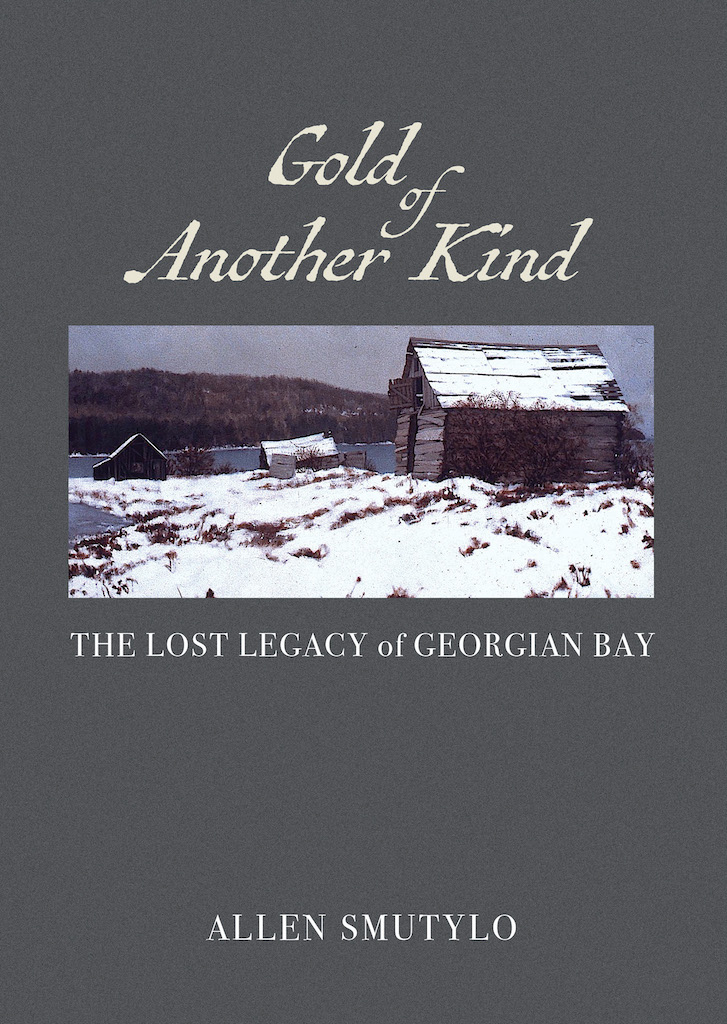

They’re all case studies for exploitation in Allen Smutylo’s latest book Gold of Another Kind. His focus is on Georgian Bay and how it has been exploited for its natural resources over the last four hundred years, namely for furs, lumber and fish. Each ‘gold of another kind’ is given its own due, its own section in the book where Smutylo diligently narrates the historical accounts while weaving in his own experiences living on Georgian Bay.

In Part I Smutylo reminds us that “[t]he Norse were the first Europeans to arrive in North America. The Thirteenth-century Greenland Saga…confirm that the Norse arrived on the North American continent primarily in search of three things: wood (for boat building), grapes (for wine), and territory…By all accounts the Indigenous population there was not entirely happy to have visitors occupying their land and helping themselves to resources. The Norse were seriously outnumbered and vulnerable…within a decade, they had abandoned their outpost and retreated back to Greenland. Five hundred years later, once again, Europeans arrived on the shores of North America. They came with a similar goal: to find and covet New World resources. But this time they didn’t leave.”

It’s a classic case of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ as Smutylo recently outlined at his book launch. If you’re not familiar with the term, it refers to the inevitable depletion of a shared resource when a group of people act autonomously in their own self-interest. Without regulations, things eventually turned tragic. I first learned about this concept in a university Economics course, and it was outlined as a tragedy of the human condition. Economics is concerned with human behaviour, and humans almost always behave in their self-interest. The problem is, there are externalities that occur in all economic activity and Smutylo makes it quite clear that the externalities from the settlers’ behaviour in this region has had catastrophic consequences.

“The human-detreeing of the Canadian landscape started in Nova Scotia in 1800, and like a voracious swarm of locusts, it spread west,” writes Smutylo in Part II. “Many factors contributed to the colossal and rapid annihilation of the towering, primordial forests around Georgian Bay and across eastern Canada. For one thing, the British Empire required wood, and lots of it – much of it earmarked for the shipyards of the Royal Navy. England had exhausted its own large timber forests and looked across the ocean to the “unlimited” forests of its North America colony to fill the void.”

“For the lumber barons though, maximizing profits was their first, last, and only consideration.”

We often speak of Canada’s romantic past, but this chapter lacks idealism; sure, the men who trapped, logged, and fished were brave and risked their lives to feed their families, but they were part of a system that lacked moral restraint.

Take for example the beaver pelt, Smutylo’s first consideration: “The early 1900s saw the beaver practically wiped out in the United States and reduced to as few as 100,000 in Canada.” Once beaver pelts became all the rage as fashionable, durable hats across Europe, there was no moderation and the pursuit became a “a titanic, no-holds barred battle over territory, furs and profits,” he says.

Much of the book outlines the relationship between the Europeans and the Indigenous. What began as a trading relationship, soon grew into catastrophe for the Indigenous through exploitation, disease, and religious doctrine; Smutylo outlines numerous instances of this, such as the Jesuit and Wendat relationship. “The Wendat and all Indigenous nations were about to face a threat far greater than proselytizing missionaries and hostile native neighbours. This new threat would have catasphrophic effect on their wellbeing , their culture and their future.”

Beyond beaver furs and lumber, Europeans took notice of the abundance of fish in the region. Part III is where the author most skillfully weaves in his own experiences living on Georgian Bay and how his perception has been shaped by the people he’s met, salt of the earth folks from the Bruce Peninsula.

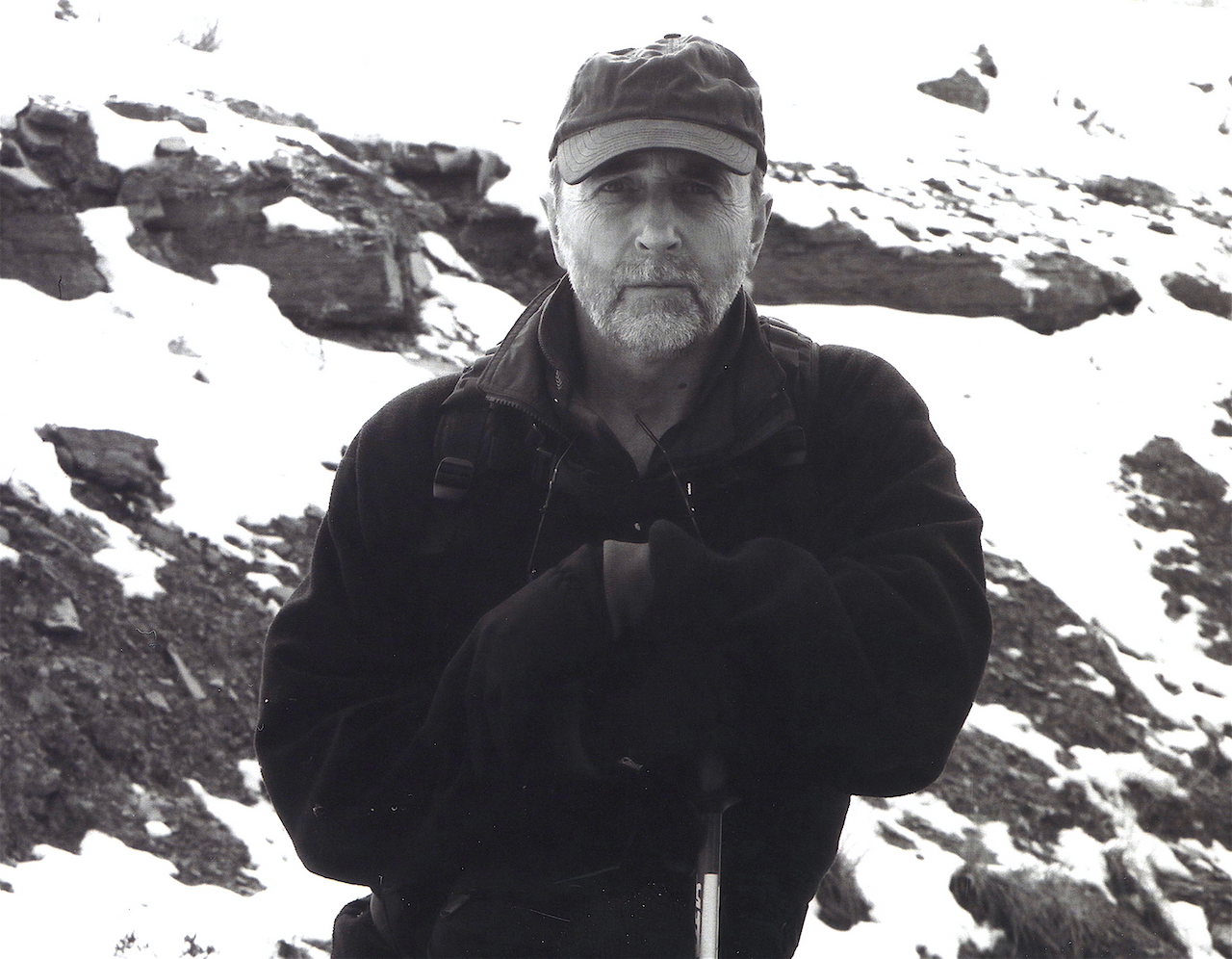

Smutylo, a highly recognized painter, moved to Tobermory from Toronto in 1970 and spent twelve years alongside Bruce Peninsula fisherman, who taught him a little about fishing, and a lot about life as a fisherman. A few of them even let him paint them, which was always his goal.

This book is a well-researched account of the history of the region that lays the facts out on the table. He strikes a balance between the industry and individuals for not only Georgian Bay, but also of other places he’s been in the world. He demonstrates a pattern of exploitation by using case studies of Newfoundland, Antarctica and Ivory Coast, all places he’s spent time. The pattern supports his thesis that this type of human activity is global in nature.

In Smutylo’s signature style, the book includes numerous paintings to help illustrate the chapters. My favourites are his portraits of the local Tobermory fisherman who personify the struggle and benefit of living on the Peninsula. Life on Georgian Bay has changed drastically over the last 200 years.

Much of the resources have been depleted, the tertiary industry is longer prevalent, and fishing is done mainly for recreation outside of a few commercial fisheries, and one can only wonder what the next ‘gold’ will be. Smutylo takes a point from other historians and philosophers that signal we humans have become ‘gods’ in our ability to subjugate the natural world, influence the survival of every other species and dictate our own future. It may be that ‘gold’ is not found in the natural world, but in the artificial one that we are hurdling towards.

If you want to understand where we’ve come from, in order to know where we’re going, I suggest reading Gold of Another Kind: The Lost Legacy of Georgian Bay. It’s a well-written narrative about this region’s history that aims to take no sides; instead, it pays careful attention to cause of effect.

There is certainly an underlying lament for the damage done in the name of greed. It’s a story that can be applied throughout history, and one sadly humans never seem to learn. In this case, it was a free-market system meeting abundant resources and acting without regulations or restraint.

It makes me wonder if the Greek philosophers had it right with their simple mantra of ‘everything in moderation’. Likely, the Indigenous proverb is one that applies more appropriately. ‘The land will take care of itself; if it is being abused it will fight back.’ This quote from Dene National Chief Bill Erasmus is especially prescient considering the events unfolding in succession around the world today. Are we seeing the Earth fight back? I’ll leave that to the scientists and scholars. I’m just a curious fella who’s pretty good at connecting the dots. This book by Allen Smutylo supplies some of those dots.

Gold of Another Kind: The Lost Legacy of Georgian Bay is available through Allen Smutylo’s website and at The Ginger Press in Owen Sound.

Written by Jesse Wilkinson